Original Article By: Aaron Severson July 23, 2010

The 1930s were full of fascinating experiments and exotic multi-cylinder Classics, but few cars of that era were more important or more influential than the humble Ford flathead V8. Cheap, pretty, and fast, it launched the American fascination with inexpensive V8 engines and spawned countless hot rods and customs. This week, we look at the 1932 Ford, its 1933–1940 successors, and the history of Ford’s famous flathead V8 — Henry Ford’s final triumph and the beginning of his downfall.

THE SELF-STYLED GENIUS OF HENRY FORD

Throughout his life, Henry Ford was a great admirer of the legendary inventor Thomas Alva Edison. Ford had worked for the Edison Illumination Company from 1891 to 1899 and Edison himself had encouraged Ford in the design of his first automobile. Ford and Edison later became friends, and Edison remained one of Ford’s greatest heroes throughout his life. In 1925, Ford actually bought Edison’s former laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, and had it painstakingly recreated in Dearborn, Michigan’s Greenfield Village.

Although Thomas Edison was and often still is considered America’s foremost inventor, his methods were surprisingly unscientific, relying not on hypothesis and experimentation, but on exhaustive trial and error, often delegated to a staff of meagerly paid workers. According to one-time employee and long-time enemy Nikolai Tesla, who wrote a scathing obituary published in the New York Times the day after Edison’s death, Edison favored the tangible, material process of invention (however cumbersomely or inefficiently executed) over academic notions of science, which he regarded with both suspicion and disdain. Tesla was hardly a neutral observer on the subject of Edison, but such characterizations are an essential part of Edison’s mythology as American folk hero — a self-made native genius for a deeply anti-intellectual culture — and, we believe, the root of Henry Ford’s admiration.

Henry Ford too was a self-made man. Although he had risen to become one of the world’s wealthiest individuals, he was raised as a poor farmer with little formal education and throughout his life he retained an outspoken contempt for the academic and intellectual. Nonetheless, by the mid-twenties, many people were already calling him a genius. In later years he would be mentioned in the same breath as Edison, something that would undoubtedly have pleased Ford greatly.

Perhaps no one was more convinced of Henry Ford’s brilliance than Henry himself. Such confidence was understandable considering his accomplishments: He had put American on wheels and revolutionized the process of mass production. John Dahlinger (who claimed to be Henry’s illegitimate son) later told author David Halberstam that Henry once described himself as the author of the modern industrial age — a claim not without justice, it must be said, but one that spoke volumes about Henry’s ego.

The consequence of this self-regard was a growing isolation. In later years, Henry surrounded himself primarily with yes-men like security chief Harry Bennett and the only qualities he truly valued in his staff were loyalty and obedience. His company was run less as a corporation than an industrial monarchy; titles and hierarchy, where they existed at all, were subject to Henry’s personal whim.

Henry Ford was above all a supreme autocrat. He could occasionally be talked into something or tricked into changing his mind, but arguing with him was perilous. He was known to fire men just for seeming too bright or having too many ideas of their own. Even Edsel Ford, Henry’s only son, was not immune, sometimes suffering humiliating abuse for daring to voice an opinion his father didn’t like.

It is often said that Henry resisted innovation. He was stubbornly opposed to four-wheel brakes, and later to hydraulic brakes. He clung to beam axles on transverse leaf springs long after most of the industry had adopted independent front suspension. He abhorred sliding-gear transmissions — in fact, he himself did not learn to use one until the late twenties — and he introduced a conventional gearbox on the Model A only under great duress. While he often justified such recalcitrance in terms that sounded conservative, we think Henry was not so much afraid of innovation as he was unwilling to follow anyone else’s lead. The reason Ford clung to the Model T’s odd planetary gearbox, for example, was that Henry hoped to introduce a self-shifting planetary transmission that would have allowed him to leapfrog all rivals. In his own mind, Henry Ford was a genius, and geniuses did not follow the crowd.

FORD’S RADICAL X-8

In the early twenties, Henry Ford’s great dream was to develop a radical new car to replace the elderly Model T, which was dangerously close to outliving its usefulness. The planned “X-car” was to be powered by an eight-cylinder radial engine, an X-8. Ford worked extensively on this design from 1922 to 1926, but it never worked satisfactorily; while air-cooled radials were common on aircraft until after World War II, the configuration posed insurmountable cooling and oiling problems for cars.

Henry was not easily dissuaded, but in 1926, he finally admittedly that the X-8 was a lost cause. Later that year, he reluctantly approved the creation of an interim four-cylinder replacement for the Model T, which became the Model A.

The Model A, introduced in late 1927, was Ford’s successor to the Model T, powered by a 201 cu. in. (3,285 cc) four with 40 hp (30 kW). Unlike the Model T, the Model A had a conventional three-speed transmission, the design of which was closely related to the transmission used in the contemporary Lincoln.

Henry hadn’t give up on the idea of a low-priced eight, however, and in 1928, he ordered engineer C. James Smith to start work on a V8 engine. That project took on a new urgency a year later when Chevrolet introduced its first six-cylinder engine. Although both Edsel Ford and production boss Charlie Sorenson pushed strongly for Ford to introduce its own six, Henry’s sole concession was to authorize some preliminary development work with no commitment to production. He was not interested in sixes; in his mind, Ford would have a V8 or nothing.

THE BIRTH OF THE FORD FLATHEAD V8

Despite his determination to offer an affordable V8, Henry Ford’s practical knowledge of that engine configuration was surprisingly limited, so after the V8 program had begun in earnest, he assigned Fred Thoms to gather and dismantle rival designs to study the existing state of the art.

The V8 engine was not terribly common in the late twenties and early thirties. Cadillac, of course, had used V8 engines since before World War I and both Lincoln and (briefly) Chevrolet had adopted them after the war, but most automakers preferred inline sixes and straight eights. V8 engines then presented several significant practical problems, among them the fact that the cylinder block was considerably more difficult to manufacture than that of an inline engine. Casting the block of a V8 engine as a single piece strained the limits of contemporary technology, so most contemporary V8 blocks were assembled in several pieces and then bolted together, which was time-consuming and expensive.

A second issue was smoothness. With a simple 180-degree (flat-plane) crankshaft, a V8 is essentially two conjoined inline fours, multiplying rather than minimizing the resultant shake. During this same period, GM briefly adopted flat-plane V8s for Viking (Oldsmobile’s short-lived companion make), Oakland, and Pontiac, but the engines were rough and unrefined and were quickly discontinued. The alternative, which Cadillac had adopted in 1923, was the 90-degree (split-plane) crank with a counterweight on each throw. This was considerably smoother than a comparable flat-plane engine (if slightly less powerful), but the split-plane crankshaft was also more expensive and complex to produce.

Such obstacles made developing a workable V8 for a low-cost, mass-production car was a challenging proposition and Henry Ford did not make it any easier. Counting Jimmy Smith’s early work, Ford had a total of four different teams working on the V8 at different times, all under Henry’s personal supervision and each largely unaware of each other’s efforts. Each team was micromanaged by Henry himself, who often complicated the engineers’ work with his arbitrary and sometimes irrational whims.

One of these, which proved the undoing of Smith’s initial design, was Henry’s unwillingness to allow the use of a water pump. We’re not sure if he was concerned about potential patent licensing issues or if he had just decided that a thermosiphon could do the same job for less money, but either way, the lack of a water pump made the engine unworkable. Henry eventually abandoned the design entirely rather than allowing Smith to develop it further.

In May 1930, Henry assigned Arnold Soth to start over, resulting in a completely new 299 cu. in. (4,905 cc) engine with a 60-degree bank angle rather than the theoretically ideal 90 degrees. This too proved unworkable; the narrow vee angle created balance problems and lubrication was hopelessly inadequate because Henry forbade the use of an oil pump. This was a curious backward step, since the Model A’s four had a conventional oil pump, but Henry was so adamant about it that he nearly fired engineer Gene Farkas for taking it upon himself to design a suitable pump.

Those issues made the Soth engine another dead end, so Henry again abandoned it and established yet another team, this one led by Carl Schultz, working with Fred Thoms and Ray Laird, to start over largely from scratch. As before, every detail was dictated by Henry Ford himself and he allowed his engineers little leeway, strenuously opposing any deviation from his specifications. The engineers worked from sketches rather than proper engineering drawings (which Henry could hardly read, in any case) and machined most of the parts themselves. The work was grueling, continuing seven days a week, and engineers rarely left even to sleep.

As Tesla later said of Edison’s methods, many of the problems Ford encountered during this difficult period could have been avoided or at least mitigated with a more methodical, less Edisonian approach to development, but Henry remained intransigent. It was some time before he even conceded the necessity of pressurized lubrication, without which the V8 would very probably not have made it to production. Moreover, he was so paranoid about the possibility of information about the engine leaking to competitors that he barely allowed his own employees to talk to each other about the project.

Schultz, Laird, and Thoms finally produced two prototype engines, one of 299 cu. in. (4.9 L) displacement and the other 233 cu. in. (3.8 L). Both were 90-degree V8s with three main bearings. Like many contemporary American engines, they used an L-head (“flathead”) layout with both intake and exhaust valves in the block. The block itself was cast as a single piece. This was not a first — GM’s Viking and Oakland V-8s, already on sale by this point, also had one-piece blocks — but it was still a notable accomplishment. Unfortunately, it was also an extremely troublesome one, thanks in no small part to the lack of precise foundry procedures. According to Charlie Sorensen, nearly half of all early castings had to be scrapped due to inaccurate core placement.

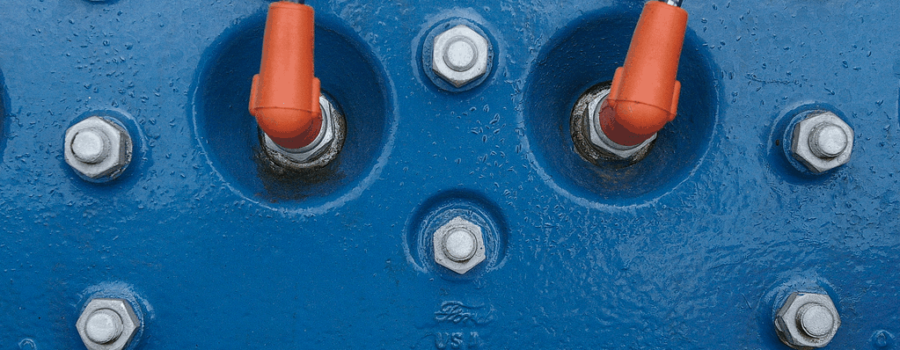

In a flathead (L-head) engine, the intake and exhaust valves are located in the block rather in the head, which serves as little more than a cover for the combustion chambers. Flatheads are cheaper and easier to manufacture than overhead valve (OHV) engines, but their thermal efficiency is poor and their breathing (volumetric efficiency) leaves much to be desired; intake mixture and exhaust gases have to follow a circuitous route in and out of the cylinders. (author diagram)

The V8 had a number of peculiar design quirks, most of them imposed by Henry himself. The exhaust was routed through the block to outboard exhaust manifolds, which made for tidy packaging and quick engine warm-up in winter, but contributed to persistent overheating problems. Compounding those was an unusual cooling system; Henry had eventually authorized the use of not one but two water pumps, but instead of pumping cold water up through the block in the conventional fashion, they were designed to draw hot coolant out of the top of the block. Other unusual features included a distributor with a novel but troublesome integral ignition coil (executed by Emil Zoerlein at Henry’s direction) and a simple single-plane intake manifold, which was cheaper than the dual-plane manifolds more common on V8 engines, but could not provide an even mixture to all cylinders. Such oddities were a product of Ford’s stubborn faith in his own instincts, which was not always justified.

The bigger engine was eventually discarded and Schultz and Laird de-bored the smaller V8 to 221 cu. in. (3,622 cc), which left more metal between the cylinder bores. Laird subsequently devised an even smaller version of 136 cu. in. (2,227 cc) displacement, which debuted in England in 1935 and in the U.S. two years later. Henry Ford committed to production of the new engines in December 1931.

Road testing, usually supervised by Ray Dahlinger (whose main occupation was managing Ford’s family farms), was no less haphazard than development. Far from an analytical evaluation of vehicle performance, the tests were primarily focused on determining whether or not parts would break under severe use. That was of course an important consideration, particularly for customers in rural areas with unpaved roads, but Ford engineers were endlessly frustrated with the lack of cogent test data. Henry Ford was unconcerned with such niceties; like the working farmer he had once been, he saw no point in wasting time or money tinkering with things that weren’t broken.

Perhaps the ultimate sign of Henry’s capriciousness — and one of the most bewildering — was one related by Harry Bennett: After months of intense secrecy, during which he threatened to fire anyone who spoke to outsiders about the V8, Henry him proudly showed off the prototypes to General Motors chairman Alfred P. Sloan. In the end, it seems, Henry’s ego won out over his sense of caution.

This is a later Ford flathead V8, distinguishable by the number of head bolts: 24 rather than 21 for pre-1938 engines. Note the unusual distributor, driven off the camshaft, and the simple exhaust manifold on the side of the head. In stock flathead engines, the exhaust for the left cylinder bank extends forward to a crossover pipe on the right side (not shown here), allowing the use of a single exhaust pipe and muffler.

THE 1932 FORD MODEL 18 AND MODEL B

When he publicly announced the new engine in an interview with the Detroit News in early February 1932, Henry Ford surprised many observers by explaining that the V8 would not appear in a new medium-priced car, as industry analysts had predicted, but a new low-priced model that would shortly replace the recently discontinued Model A.

In fact, some within Ford, notably Edsel, were already pushing Henry to introduce a middle-class car priced between Ford and Lincoln, but that effort would not come to fruition for another six and a half years. In view of the worsening economic depression, that was perhaps just as well, but the truth was that Henry was just not interested in offering such a car. Despite his great wealth, his principal preoccupation remained cheap cars for working-class people and particularly farmers; even Lincoln, which Ford had purchased in 1922, had always been primarily Edsel’s domain. In Henry’s view, the central purpose of the V8 had always been to trump Chevrolet, not to join the herd of middle-class makes.

The 1932 Ford itself was publicly revealed at the end of March and began appearing in showrooms on April 2. Their launch drew widespread national attention, in no small part because the Model A had actually been out of production for nearly six months and both Ford customers and dealers were impatiently wondering what would take its place. Although Chevrolet had overtaken Ford in sales volume in 1931, Ford still had many loyal customers and the prospects of an inexpensive eight drew great interest and thousands of advance orders.

The new cars themselves made a strong impression. For one, they were rather pretty, with styling reminiscent of the big Lincoln (a point we’ll discuss further below). The principal attraction, of course, was the new V8 engine, but there were also other attractions: You no longer needed to manually advance the spark, second and third gears were now synchronized, and a conventional fuel tank had replaced the Model A’s gravity-feed cowl tank (which had been both complex to manufacture and a potential fire hazard in a collision).

The 1932 Fords were divided into two series: the four-cylinder Model B and the V8-powered Model 18, both offered with an extensive choice of body styles. The Model B, offered mostly to forestall problems with either the public acceptance or the production of the new V8, used a much-improved version of the Model A’s familiar 201 cu. in. (3,285 cc) four, now making a claimed 50 hp (37 kW). The Model 18 had the V8, which displaced 221 cu. in. (3,622 cc) and made an advertised 65 hp (49 kW) and 130 lb-ft (176 N-m) of torque.

As was customary for Ford, the new cars were still very affordable; in fact, the cheapest 1932 Model B roadster was actually $20 less than the equivalent 1931 Model A. The Model 18 cost $50 more than the equivalent Model B, but was still aggressively priced, costing only $15 more than a comparable 1932 Chevrolet and undercutting Plymouth by almost $100. (If the latter sounds trivial today, we should note that Ford’s price advantage over Plymouth was equivalent to almost $1,500 in inflation-adjusted modern dollars.)

This is a 1932 Ford Model B rumble seat roadster, distinguishable from the slightly more expensive cabriolet by its folding windshield. The Model B was nearly identical externally to the V8-powered Model 18, sharing its 165.5-inch (4,204mm) overall length and 106-inch (2,692mm) wheelbase, but was somewhat lighter and $50 cheaper.

The four-cylinder Model B was anemic compared to its Chevrolet and Plymouth rivals, but the Model 18 was another matter. The flathead V8 was not dramatically more powerful than Chevy’s 194 cu. in. (3,184 cc) six (with 60 hp/45 kW) or Plymouth’s 196 cu. in. (3,213 cc) four (with 65 hp/49 kW), but V8 Fords were up to 280 lb (127 kg) lighter than either competitor, making for a significantly better power-to-weight ratio. Britain’s The Autocar found that a V8 Ford cabriolet could reach a top speed of nearly 80 mph (126 km/h), brisk business for an inexpensive car of the time. The Ford was nimble, too, although it was not particularly quiet or smooth.

Despite its sub-par acceleration, the Model B accounted for nearly 76,000 sales in 1932, compared to more than 179,000 V8s. While the V8 was clearly the more popular of the two engines, its early production problems meant that there initially few to go around. Furthermore, while the V8’s $50 price premium was eminently reasonable, it was still a lot of money for working-class buyers in the depths of the Great Depression, particularly for a completely new and untried engine.

1932 Ford Model B engine

The Model B’s engine was a heavily revised version of the four used in the Model A. Its bore and stroke were the same, but it had a new crankshaft, larger main bearings, a higher compression ratio (a still-modest 4.6:1), and a bigger carburetor. Although Ford advertised it at 50 hp, its gross rating was actually 52 hp (39 kW), compared to only 40 hp (30 kW) for the Model A. (Photo: “Ford Model B-2” © 2007 Don O’Brien; used with permission)

FLATHEAD TEETHING PAINS

If buyers were wary of the new V8, they had ample reason. Rushing an entirely new engine into mass production in only 16 months would have been daring even if the development and testing process had been less erratic. In a taped interview with Owen Bombard in the early fifties, engineer Larry Sheldrick lamented that Ford had basically used its customers to do the testing that should have been done by the factory.

The 1935-1936 Fords were the last designed by Briggs Mfg. Co. Stylist Phil Wright designed the very successful 1935 model, while the 1936 car was facelifted by Bob Koto. Note the small grilles in the fender ‘spats’; these cover the twin horns included with the DeLuxe trim level.

The early V8’s problems were numerous. Block cracking was common and piston failure became almost routine. Oil consumption was often massive; without frequent top-ups, the entire 4-quart (1.9-liter) capacity might be consumed before the first tank of fuel was gone. The fuel pump was prone to vapor lock in the summer and freezing in the winter. Overheating remained a constant issue, particularly on the more heavily stressed commercial models.

Some, although by no means all, of these problems were rectified in the first year or two of production. Charlie Sorenson developed new casting methods that alleviated the block-cracking problems, while Henry Ford eventually relented on a few of his less-successful design demands, including the single-plane intake manifold and, by 1937, the high-mounted water pumps. By 1934, the V8 had become a reasonably trustworthy engine, although Ford continued to make running changes throughout the flathead V8’s lifetime — usually though not always for the better.

The teething pains did not affect the V8’s popularity, which took off quickly once the early production delays had been resolved. Sales of the Model B tapered off quickly after 1932 and Ford dropped it entirely in March 1934, but it took less than a year to sell a million V8s. By June 1940, the total had hit 7 million.

Wind wings were included on the 1936 Ford DeLuxe roadster, but side windows were not; note the snaps for the side curtains, not fitted here. This car wears an authentic Cordoba tan paint job with Poppy red pinstripes. Cordoba tan, incidentally, was the only factory color available for station wagons at this time.

THE BANK ROBBER’S CHOICE

Ford brochures claimed that the new V8 set a new standard for performance in mass market cars and that became even more true as Ford began to address the engine’s early problems. Along with greater reliability, the engineers found more power: 75 hp (56 kW) in 1933 and 85 hp (63 kW) thereafter. (For reasons that remain unclear to us, Ford claimed 90 hp (67 kW) in 1936, but returned to the 85 hp rating the following year.) While Ford never had a vast advantage over Chevrolet and Plymouth in rated horsepower, it was consistently the quickest member of the “Low-Priced Three.”

Ford cars grew steadily bigger throughout the thirties. The 1936 models were 182.8 inches (4,642 mm) long on a 112-inch (2,845mm) wheelbase, 17.3 inches (438 mm) longer and around 280 lb (127 kg) heavier than the ’32. (That’s one of the reasons hot rodders have long preferred the ’32 Ford.) Starting in 1935, Ford’s transverse leaf springs were mounted outboard of the axles, increasing the spring base in search of a softer ride. Brakes were still mechanical, a feature Ford advertised proudly as safer than hydraulics.

Ford cars grew steadily bigger throughout the thirties. The 1936 models were 182.8 inches (4,642 mm) long on a 112-inch (2,845mm) wheelbase, 17.3 inches (438 mm) longer and around 280 lb (127 kg) heavier than the ’32. (That’s one of the reasons hot rodders have long preferred the ’32 Ford.) Starting in 1935, Ford’s transverse leaf springs were mounted outboard of the axles, increasing the spring base in search of a softer ride. Brakes were still mechanical, a feature Ford advertised proudly as safer than hydraulics.

Even in stock form, V8 Fords were quickly embraced by performance-minded customers. The notorious bank robber John Dillinger preferred Fords for fast getaways, although the well-known telegram he purported sent to Henry Ford was apparently a hoax. Hot rodders were even more enthusiastic. People had hopped up Model Ts and Model As, mostly because they were cheap and readily available, but the V8 provided a much better foundation. For a modest investment of time and money, the flathead Ford could be made to produce substantially more than its rated output. By the late thirties, there was a growing cottage industry churning out performance parts for Ford V8s, ranging from camshafts and intake manifolds to more exotic modifications, like the overhead-valve “Ardun” heads developed by future Corvette engineer Zora Arkus-Duntov. Ford’s smaller 136 cu. in. (2,227 cc) V8-60, added in 1937, had fans of its own. Although it was underpowered in stock form, it later became very popular in midget racing.

The flathead’s popularity only increased after the war. With buyers clamoring for new cars, a decent-running prewar V8 Ford could be had for as little as $15, part of the reason it became so ubiquitous in the postwar hot rod and custom scene.

In a later era, Ford Motor Company would certainly have promoted this sporty image, but Henry Ford was never interested in marketing or promotions, leaving advertising decisions to Edsel. While Ford ads of the thirties made decorous mention of the V8’s brisk pickup, they were just as likely to emphasize practicality, urbane road manners, or chic styling.

HENRY FORD’S DECLINING YEARS

Even with the V8, it took Ford until 1934 to pull even with Chevrolet in sales and until 1935 to regain the number-one slot. Although Ford remained America’s best-selling automotive nameplate until 1938, the margin was often narrow and Ford didn’t regain the top slot again until after the war.

Ironically, Ford’s greatest commercial strengths during this period were in areas Henry Ford either hadn’t considered, like performance, or didn’t care about, like styling. The V8 had been his last great achievement; Ford had lost touch with the market he once commanded.

Henry grew even more obdurate as he approached his 75th birthday in 1938 and there were signs that his stubbornness may have been a sign of dementia. Although he finally consented to the use of hydraulic brakes, he wasted years on an abortive five-cylinder engine rather than the six Edsel still insisted they needed. Edsel eventually ordered Larry Sheldrick to design a six-cylinder engine, but the elder Ford insisted on developing a competing overhead-cam design, perhaps still looking for something that would reaffirm his engineering prowess. The OHC engine was a failure and Sheldrick’s six went into production, replacing the smaller V8 for 1941. Henry viewed this as treachery on Sheldrick’s part and it probably contributed to Sheldrick’s firing in 1943, although the more immediate provocation was Henry’s discovery that Sheldrick and Edsel had been discussing postwar designs with Henry’s grandson, Henry Ford II, without Henry’s permission.

This 1940 Ford DeLuxe station wagon shows off its front-end styling, an awkward facelift of the lovely ’39 with new sealed-beam headlights. Ford practice at this time was to use the previous year’s DeLuxe styling as the next year’s Standard, which left the 1940 Standard cars looking somewhat better than their more-expensive mates. During this period, Ford was the industry leader in station wagons, but they were still considered commercial vehicles and sold in modest numbers. Front-end styling is shared with the sedans, although the body aft of the cowl is obviously quite different.

This 1940 Ford DeLuxe station wagon shows off its front-end styling, an awkward facelift of the lovely ’39 with new sealed-beam headlights. Ford practice at this time was to use the previous year’s DeLuxe styling as the next year’s Standard, which left the 1940 Standard cars looking somewhat better than their more-expensive mates. During this period, Ford was the industry leader in station wagons, but they were still considered commercial vehicles and sold in modest numbers. Front-end styling is shared with the sedans, although the body aft of the cowl is obviously quite different.

Late in his life, Henry Ford became increasingly dependent on security chief Harry Bennett, who had been Ford’s strong-arm man and union buster since 1917. Bennett fed his boss’s paranoia for his own benefit, taking it upon himself to protect the old man from all enemies, real or imagined — a category that conveniently included anyone who threatened Bennett’s power or position. Henry gave Bennett enormous latitude, even over Edsel, whose health was increasingly poor.

Although only in his 40s, Edsel had suffered for years from recurring stomach ulcers and in 1942 was diagnosed with stomach cancer. His condition deteriorated rapidly, exacerbated by a bout of undulant fever, allegedly contracted after drinking unpasteurized milk from one of the family’s farms. He died on May 26, 1943, at the age of 49. Upon his death, his father resumed the role of president, the position Edsel had held (at least in name) since 1919. A week later, he appointed Harry Bennett to the board of directors.

Although Henry Ford hated Franklin Roosevelt and had little enthusiasm for the war, the Ford Motor Company was one of America’s largest wartime contractors. One-time Ford executive William “Big Bill” Knudsen, who headed the Roosevelt administration’s National Defense Advisory Commission, had dealt primarily with Edsel and was uneasy about the ramifications of Edsel’s death. Aside from Henry’s possible dementia, he was almost 80 years old. If he died or became incapacitated, it was possible that Ford Motor Company would collapse, which would be strategically disastrous, or that control would fall to Harry Bennett, which Knudsen did not consider a palatable alternative.

Eleanor Clay Ford, Edsel’s widow, and Clara Ford, Henry’s wife, did not like that idea any more than Knudsen did. In August 1943, they arranged for Henry Ford II, Edsel’s eldest son, to be released from the Navy. In December, the younger Henry officially became a Ford vice president.

The intention was for Henry Ford II, then only 26 years old, to become his grandfather’s apprentice. Harry Bennett and Charlie Sorenson had other ideas and made every effort to shut the younger Henry out, constantly attacking and belittling him the way they had his father. The younger Henry had some allies, including sales chief John Davis, but Henry’s grandfather offered little help. By then, the elder Henry’s trust in Bennett was unwavering, although Bennett succeeded in turning him against Sorenson, who was forced to retire in 1944. Henry’s shaky physical health didn’t help; he suffered a stroke in early 1945.

According to author David Halberstam, it was Eleanor and Clara who finally broke the deadlock, presenting Henry with an ultimatum: If he would not step down and let his grandson take real control of the company, Eleanor would sell all of her and Edsel’s Ford stock, which represented about 45% of the company’s total shares, and allow outsiders to take a hand. Although there’s little question that Eleanor and Clara were dismayed by the situation, Henry Ford II himself denied that story; he maintained that it was he and a small group of allies, including Davis and John Bugas, who convinced the elder Henry that his day was done.

Either way, the result was the same: Henry Ford reluctantly announced his resignation on September 21, and Henry Ford II, then only 27 years old, became president. Bennett was the next to go, followed by many of his cronies. With their exit, the younger Henry began the difficult task of rebuilding and reorganizing.

Henry Ford died on April 7, 1947. He had left his grandson a company in ruins, losing a terrifying amount of money each month and in such organizational chaos that just assessing the magnitude of the financial crisis was a major undertaking. Recognizing that it was beyond his ability, Henry Ford II recruited former Bendix executive Ernest R. Breech as his executive vice president and de facto regent. Ford subsequently hired a host of former GM executives and designers as well as a group of bright young ex-military officers known as the Whiz Kids (of whom we spoke more in our article on the Ford Falcon. They spent the next decade setting the corporation on a more orthodox, fiscally responsible, conservative course.

FORD AFTER FORD

Bob Gregorie did not last long at Ford after the death of his patron; he was fired in late 1943. In 1944, he returned at the request of Henry Ford II, but they never established the same kind of congenial working relationship that Gregorie had had with Edsel. Henry Ford and Ernie Breech were uncomfortable with Gregorie’s postwar designs and his tenure was short. He resigned in December 1946 and moved to Florida, where he became a yacht designer; his final Ford designs were the 1949 Mercury and Lincoln.

The small V8-60 disappeared from American Fords after 1940, but continued to be used by Ford’s European subsidiaries. In 1954, Ford sold its French operation to Simca, which continued to manufacture and use the 136 cu. in. (2,227 cc) V8 until 1960.

The bigger flathead V8, enlarged to 239 cu. in. (3,910 cc) for Mercury and postwar Fords, remained Ford’s mainstay well into the 1950s. From 1948, there was also a scaled-up 337 cu. in. (5,518 cc) version used in heavy trucks and 1949-1951 Lincolns. American production of the flathead ended in 1953, although Ford Australia and Ford Canada continued to produce it for an additional year. As with the small V8, Ford subsequently licensed the flathead engine to Simca, which built beefed-up versions for military trucks until the early 1990s.

This battered and rusty specimen is a 1953 Ford Mainline Tudor sedan, one of the last U.S.-market Fords to carry the familiar flathead V8. The newer inline six actually gave similar performance and better fuel economy, but many buyers preferred the V8, which now claimed 110 hp (82 kW). (Mercurys had a 256 cu. in. (4,194 cc) version of the flathead with 125 hp (93 kW), but that version was not available in Fords, at least not as factory equipment.)

Even today, there remains a thriving business in flathead Ford hop-up parts, but Ford’s subsequent OHV V8s never developed the same loyal following. In 1955, the new Chevy V8 captured the fancy of the hot rodder crowd, a market Ford didn’t really reclaim until the 5.0 L Fox Mustangs of nearly 30 years later.

The reign of Henry Ford II, who retired in 1980 and died in 1987, was in many respects the diametric opposite of his grandfather’s era. Under Henry II, Ford emphasized all the values Henry I had disdained, such as marketing and financial controls; the company became fiscally responsible to a fault. The consequence, however, was the loss of most of the previous era’s strengths. For all the company’s newfound ability in product development, Ford rarely innovated in either styling or engineering. Its specialty models, like the Thunderbird and Mustang, were attractive, but the styling of Ford’s bread-and-butter products was generally staid. Ford was good with little details, like double-sided keys and clever two-way tailgates for station wagons, but there were no more great leaps like the flathead V8. In technology, Ford no longer invented, it refined; it no longer led, it followed.

The tragedy of Henry Ford I (and we are inclined to look at it as a sort of Greek tragedy) is that in some ways, he was a genius. He was hardly a model human being — by many accounts cruel and sometimes sadistic, an anti-Semite and a bully — but many of his ideas about manufacturing and low-cost transportation were legitimately revolutionary. The problem was that he was not the kind of genius he thought he was; he was not Thomas Edison. The more he became convinced that he was, the more he blinded himself to his actual talents. The cost was substantial: He undermined his own son, almost did the same to his grandson, and came perilously close to ruining the company he had worked so hard to build.

It’s tempting to wonder what might have happened if Henry Ford had cultivated his staff and his son as allies rather than treating them as servants and if he had not retreated into paranoid, self-justifying insularity. Some of his wilder ideas might well have worked even if he himself didn’t know how to make them work. Certainly, the fortunes of the Ford Motor Company would have been very different and perhaps American business would have taken a different course as well. Instead, Detroit — and eventually the rest of the business world — decided it had had enough of the stubborn engineers and contrarian entrepreneurs who’d built the auto industry, retreating to the comforting predictability and more manageable ambitions of accountants and finance men.

While we can’t admire Henry Ford the man, we’re inclined to think that the world needs visionaries, people who are willing to swim against the tide and create new paradigms. Sadly, the modern world has little place and less patience for such dreamers, and we think the excesses and irrationality of people like Henry Ford had something to do with that. His achievements were inarguably great, but the shadow cast by his failures has proven long indeed.

Original Article By: Aaron Severson July 23, 2010

NOTES ON SOURCES

Our sources on the life of Henry Ford and development of the Ford cars included the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, Cars That Never Were: The Prototypes (Skokie, IL: Publications International, 1981), and Encyclopedia of American Cars: Over 65 Years of Automotive History (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 1996); Harry Bennett with Paul Marcus, We Never Called Him Henry (New York: Fawcett Publications, 1951); Douglas Brinkley, Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress (New York: Viking Press, 2003); Arch Brown, “comparisonReport: 1931 Chevrolet, Ford and Plymouth,” Special Interest Autos #77 (September-October 1983), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords: driveReports from Special Interest Autos Magazine, eds. Terry Ehrlich and Richard Lentinello (Bennington, VT: Hemmings Motor News, 2001); “Dominant Rivalries,” Special Interest Autos #174 (November-December 1999), reprinted in ibid, pp. 52-67; “1932 Model B Ford: Son of Model A,” Special Interest Autos #130 (July-August 1992), reprinted in ibid, pp. 30-35; “1941 Lincoln Continental: Edsel Ford’s Legacy,” Special Interest Autos #122 (March-April 1991), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Lincolns: driveReports from Special Interest Autos magazine, eds. Terry Ehrich and Richard Lentinello (Bennington, VT: Hemmings Motor News, 2002), pp. 28-35; and “SIA comparisonReport: 1941 Chevrolet, Ford, and Plymouth,” Special Interest Autos #69 (May-June 1982), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 108-115; Arch Brown, Richard Langworth, and the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, Great Cars of the 20th Century (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, Ltd., 1998); David R. Crippen, “Reminiscences of Eugene T. Gregorie,” 4 February 1985, Automotive Design Oral History Project, Accession 1673, Benson Ford Research Center, www.autolife. umd.umich. edu/ Design/Gregorie_interview.htm (transcript), accessed 25 October 2009; James M. Flammang, David L. Lewis, and the Auto Editors of Consumer Guide, Ford Chronicle: A Pictorial History form 1893 (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 1992); Ken Gross, “1939 Ford Woody: Henry’s Lovable Lumber Wagon,” Special Interest Autos #63 (May-June 1981), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 92-99, and “1940 Ford—The Deliverer,” Special Interest Autos #33 (March-April 1976), reprinted in ibid, pp. 100-103; David Halberstam, The Reckoning (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986); Maurice Hendry, Cadillac: Standard of the World: The Complete History, fourth edition (Princeton, NJ: Automobile Quarterly, 1990); Dave Holls and Michael Lamm, A Century of Automotive Style: 100 Years of American Car Design (Stockton, CA: Lamm-Morada Publishing Co. Inc., 1997); Tim Howley, “SIA comparisonReport: The New and the Old: 1952 Ford Six vs. V-8,” Special Interest Autos #143 (September-October 1994), reprinted in The Hemmings Motor News Book of Postwar Fords, pp. 28-38, and “1953 Ford: The Final Flathead,” Special Interest Autos #56 (March-April 1980), reprinted in ibid, pp. 40-47; Lee Iacocca, Iacocca: An Autobiography (New York: Bantam Books, 1984); John Katz, “Fabulous Flathead,” Special Interest Autos #178 (July-August 2000), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 86-92; Beverly Rae Kimes, ed., Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942, Second Edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, Inc., 1989); Michael Lamm, “Henry Ford’s Last Mechanical Triumph” (which was based in part on tape-recorded interviews with engineers Gene Farkas, Fred Thoms, and Larry Sheldrick, conducted by Owen Bombard of the Ford Archives between 1951 and 1958), Special Interest Autos #21 (March-April 1974), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 36-43; “Model A: The Birth of Ford’s Interim Car,” Special Interest Autos #18 (August-October 1973), reprinted in ibid., pp. 12-21; “1932 Pontiac V-8,” Special Interest Autos #13 (October-November 1972), reprinted in The Hemmings Motor News Book of Pontiacs: driveReports from Special Interest Autos magazine, eds. Terry Ehrich and Richard Lentinello (Bennington, VT: Hemmings Motor News, 2001), pp. 4-10; and “Two Look-Alikes: Ford & Citroen,” Special Interest Autos #9 (January-March 1972), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 44-51; Michael Lamm and David L. Lewis, “The First Mercury & How It Came to Be,” Special Interest Autos #23 (July-August 1974), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Mercurys: driveReports from Special Interest Autos magazine, eds. Terry Ehrlich and Richard Lentinello (Bennington, VT: Hemmings Motor News, 2002), pp. 4-11; David L. Lewis, “Ford’s Postwar Light Car,” Special Interest Autos #13 (October-November 1972), pp. 22-27, 57; Don MacDonald, “Those Wild, Wild Getwaway Cars!” Motor Trend Vol. 18, No. 10 (October 1966), pp. 72-74; “1949 Ford driveReport,” Special Interest Autos #5 (May-June 1971), reprinted in The Hemmings Motor News Book of Postwar Fords: driveReports from Special Interest Autos magazine, eds. Terry Ehrich and Richard Lentinello (Bennington, VT: Hemmings Motor News, 2000), pp. 10-16; George Mattar, “Collector Buyer’s Guide: 1932–1934 Fords,” Hemmings Classic Car #12 (September 2005), pp. 82–87; Paul McLaughlin, “Beauty, Comfort, and Safety: The Story of the 1935 Ford,” Collectible Automobile Vol. 19, No. 5 (February 2003), pp. 40–51; “SF Flatheads: History,” SF Flatheads, n.d., www.sfflatheads.com, accessed 26 October 2009); Charles Sorensen, My Forty Years With Ford (New York: W.W. Norton, 1956); “The Life Cycle of the Ford Flathead V8: 1932-1953,” 35Pickup, May 2002, www.35pickup. com, accessed 26 October 2009); Nikolai Tesla, “Tesla Says Edison Was an Empiricist,” New York Times 19 October 1931, www.nytimes. com, accessed 26 October 2009; Josiah Work, “1935 Ford Model 48: The Sleeper Among Flatheads,” Special Interest Autos #114 (November-December 1989), reprinted in The Hemmings Book of Prewar Fords, pp. 68-75.

Original Article By: Aaron Severson July 23, 2010