This article was written by Jasperforty

I’ve always been an inveterate tinkerer and have a long love of engineering and machinery. I started my mechanical career with wind up gramophones and old cameras, moved on to bicycles, then a 1958 Triumph Terrier motorcycle that I rebuilt, got running and then used to bounce around the hills of Wales aged 15. I moved on after school to build a VW Beach Buggy in the street outside my parent’s house in North London, the discarded body from the VW beetle cut into small enough pieces to be put out with the garbage. Volkswagen’s always had a special place in my heart. I currently own a Golf and a Carravelle, and in the garage I have a VW-based 356 which I painted with Escher Lizards so it could be a facsimile of Thursday’s Car. It’s nearly at the end of the two year rebuild.

Ford Model T’s, however, are something else entirely. Idiosyncratic might be the word – bizarrely thought out and full of ancient engineering concepts and solutions that were quite normal for 1908 when it was designed. You can’t actually drive a Model T without training and a great deal of concentration and practice – the ‘clutch’ pedal (actually a ‘drive’ pedal in the T) works in the opposite sense, so instinctively trying to disengage the engine actually engages it – not for the faint-hearted at road junctions, and all Model T owners, in their ‘getting to grips with it’ days, have almost certainly attempted to drive through the back of their garage. More about this later, but there is no gear stick – just a plethora of pedals staring at you from the floor of the car. After fourteen years of ownership I can move seamlessly between my others cars and this one, but it took a while.

It seems illogical now, but it was totally logical then. When Henry Ford designed the Model T as a car for the masses, it pretty much replaced the horse. There were no roads, no driving tests or licenses, and the T was designed pretty much for someone who had never driven before, and with little or no training. Manual shift gearboxes and ‘letting out the clutch’ were for a driving-savvy population, the Model T was for the beginner and could be driven competently with only a large field and thirty minutes of your time. It is basic and hard-wearing, but also requires specific handling requirements: In the winter it helps to jack up a rear wheel to assist with cold starting and badly adjusted bands would have it nudging forward as you hand started it, pinning you against a wall ‘like a horse nosing for an apple’. It is slow, and noisy, and has no heater or demister, or wipers. The lights are terrible, it is dangerous at almost any speed, has appalling brakes. It is quirky and recalcitrant, obsolete and constantly in need of fettling – I had to have one.

I’ve owned mine since 2008 and in that time have extensively modified her for competing in Vintage Trials, as well as generally tootling around, in which it never fails to draw a crowd and cheery waves from five-year-olds. In the vintage car fraternity we kind of take it as read that these things need to be driven on the roads, or, more accurately, the roads need them to drive on them, in order to link us and our past. When you see a parade of vintage cars burbling past, think that you are seeing a museum in reverse – not one that you have to visit, but one that comes to you, randomly.

This entry might seem a little boring to anyone who doesn’t like cars and old things and engineering, but it is very much part of me: The fascination of thinks technical and the diligence and curiosity to take something apart to see how it works are not just enjoyable, but offer transferable skills.

Tinkering is not just about figuring stuff out and the historical viewpoint, but also a sense of the elegance of engineering solutions – something that I enjoy a great deal with writing. The way a story slots into place and the sometimes complex maneuverings and ingenious use of the tools available are not dissimilar to the awe one feels when realizing how the complex sliding gears on a gearbox manage to work, nor how one can find a simple solution to a modification issue that was solved with a imaginative approach, skill and a lot of thought.

It’s also useful to have a ‘how hard can it be?’ approach to task. While admitting this approach can somehow allow you to fall on your face, that’s often a good thing: Failing shows that you are trying. Multiple failures show you are not one to easily give up.

Having knowledge over a particular field is also a great leveller, and can introduce you to people to whom otherwise you might not meet. The Model T fraternity covers a broad cross section of political views, groups and opinions, and straying outside one’s usual group to another linked by a random common factor can only be for the good.

In the same way you can also find yourself within a large and very extended family. If I break down in my T or my old VW, I will rarely have to wait twenty minutes before someone stops to see if I need assistance – and the offer of a tow and a fully equipped garage – the same way I do for others. Once, I came across a fresh-faced Model T owner who was frustrated with a slipping clutch. That evening, I popped over to show him how you can adjust the drive – a trick that all T owners need to know. This is not unusual.

I can’t imagine my life without several wheeled vehicles that weren’t hanging around needing fixing; sometimes the fixing and tinkering is the best bit of it, the pleasure one can get to utilize diligence and knowledge and experience to make an impossible job look easy.

And who doesn’t enjoy that? Whether its enacting new legislation, keeping a patient alive beyond all odds, making a garden work in difficult soil or, well, pretty much anything you enjoy doing that requires application and thought. Challenges are fun, challenges are good, challenges make us realist that there is little we can’t achieve.

The Ford model T has a lot to answer for. Along with the Colt .45, electric light globe, dynamo, jet-engine and phonograph, it probably did more to shape the economic, social, political and environmental issues of the globe than any other single invention. It gave us unparalleled freedom, independence and mobility, created countless jobs, increased technological understanding and has been the furnace of industry for a century. On the downside, the automobile kills approximately 1.2 million people each year in accidents, is disproportionately voracious of raw materials, contributes seriously to global pollution, and the demand for its fuel has caused war, tension, and increased global conflict.

And this innocuous-looking car, a visionary industrialist and a willing public started all that. By the time Henry Ford built his ten millionth vehicle, 90% of the world’s cars were a Ford Model T. If Henry hadn’t been so immovable in his views and hung on to his beautiful obsolete design as ‘all that a man could want’, it is likely that every car today would be one of his, and not called a ‘car’, but a ‘Ford’. (Henry Ford was both a visionary and a monster. He remains a revered figure for engineering and marketing in American industry He almost single-handedly created a consuming American middle class, but was strike-buster, advocated almost suffocating paternalism to his workers and was rabidly anti-Semitic. He was actually decorated by the Third Reich, and is even given a glowing name check in Mein Kampf . )

The Model T went into full production in 1908, and aside from a few body-styling modifications remained unchanged in basic layout until 1927 and fifteen million units later. Looking around the car you may be surprised at how agricultural the engineering is – from the rudimentary U-channel chassis buck-riveted together to the simplicity of the suspension and running gear, and rough-cast iron parts. You may indeed be forgiven for thinking this was simply the quality of engineering of the day – but you would be wrong. Cars of great quality were being made at this time, and although Ford did significantly assist with the mass-manufacture of standardized parts, most of this car was built to one overriding central tenet- extreme cheapness and speed of manufacture.

The Ford model T was the Yugo of its day; a cheap car for the masses that could be churned off the production line as quickly and as cheaply as possible. The old adage ‘any color as long as it’s black’ may have been true, but only because of the speed at which black paint dried – it’s quickest.

At its height, the Ford factory at Deerborn was exchanging raw materials to Model T in under 72 hours, and a complete car could be assembled in 93 minutes. In 1925 a basic T would cost $300, which is a rock-bottom £1600 today, even in inflation-adjusted figures.

It’s not hard to see where savings were made. You will note that each axle is supported beneath a single transverse semi-elliptical spring. The ride was worse than longitudinal double-elliptical, but it used a lot less metal. The sheet steel is all one gauge. The same steel in the body panels were also used to make clutch-plates. Wooden floorboards were often made from the packing cases in which parts from subcontractors were delivered.

But although a skimper in many areas, Henry Ford insisted that important and hard-wearing parts of the car were made of high-grade vanadium steel – the front axle was so strong it could be cold-twisted eight times without fracture. The stub-axles, springs, crank, epicycle gears and other parts are also of this steel. Not cheap, but reliable, and the Model T, maintained properly, would run and run and run.

This car was built on December 14th 1918 (so she’s technically Edwardian, rather than Vintage), and was probably an open touring, as most of the vehicles at that time were either this or the two seater runabout as it was a cheaper body to make, and the price could be brought down even further by adding the hood as an ‘extra’. Henry decided that instead of designing the car and then seeing how much it would cost, he would think of a cost and then build the car to that target.

To do this he not only streamlined production (using the moving belt of a slaughter-house as inspiration) but also subcontracting parts to smaller companies, and unusually, paying his workers more money in order that they might be able to afford one of the cars they were building, and thus increase the market, and further lower the cost. Anathema at the time, but probably one of the greatest counterintuitive moves in American manufacturing history ever made. The more cars he could make, the cheaper they would become.

Ford cars then have pretty much the same cachet as they do now – a cheap and cheerful car that while not of the highest quality, will certainly get you around. Often drivers would buy a new T every year if for nothing but the fresh tyres and a new set of transmission bands, creating an industry that until then had never existed – a burgeoning second-hand car market. Soon, you could own a Ford even if you couldn’t afford a new one, and by the early twenties America was awash in used ‘flivvers’ or ‘tin lizzies’.

By the 1920s, with Ts in abundance, it was the turn of the amateur racers to enter the picture, as the plethora of cheap Ts positively begged to be raced, and teenagers being teenagers, cars were initially stripped of their body and hacked around the oval horse-track that would have been on the edge of most towns.

Incidentally, oval track racing is still with us today: We call it autocross or speedway in the UK, while the famed Indianapolis 500 is essentially an out-of-town pony circuit, just bigger, faster, larger and with banked corners.

Pretty soon, amateur engineers were trying to think up ways to liven up the performance of their cars in order to give them an edge at the racetracks. Cylinder heads were skimmed to give higher compression, and combustion chambers smoothed out to allow the asthmatic side-valve engine to breathe better.

Cars were lowered to give them better handling, as the ground clearance of the first Ts was almost a foot, something which was considered necessary at the time, given the poor quality of the world’s roads. Indeed, very early Ts were right hand drive in America, as it was considered more important to keep an eye on the verge for potholes than for overtaking.

Third-party manufacturers had been selling alternative parts for the model T since it first came on sale. As early as 1914 you could buy aftermarket timers, shock-absorbers, horns, rear-view mirrors, carburetors, ‘no-shimmer’ stub axles and improved transmission bands. The list grew longer and longer.

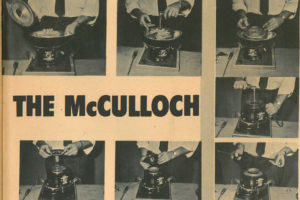

It wasn’t too long before companies sprang up to service the amateur racing market, and this is pretty much where my car fits into the story. By 1921 this car was stripped down and converted into a racer, and if you are not yet bored to tears, I’ll tell you a little bit about the engine and gearbox.

Engine: The Model T Ford has a 2.9 litre in-line four cylinder engine with the then novel idea of a removable cylinder head, and all four cylinders cast in one block. The crank had three white-metal bearings, and the oil was splashed around the sump and enclosed gearbox by the action of the crank. The carburetor was mounted low down on the right and fed the engine via a torturous manifold, and gases were ejected by an equally torturous route out.

In this manner, the engine, in stock configuration, developed 20 HP, had a top speed of about 40-45 MPH with a fuel economy of around 25 miles per gallon – better than many US cars today. The low power was supplemented by a huge amount of torque and a broad power band – which allowed Henry to get away with his ‘Three Speed’ gearbox, which was actually only two forward speeds, and a reverse.

The cylinder head on this car is called a Frontenac head and was a designed and manufactured by Louis and Arthur Chevrolet, two French immigrants who had been modifying Fords since the early teens, and from the revenue and expertise earned here, went on to found Chevrolet Motors. This head is an Overhead Valve System, and bolts directly on top of the Model T cylinder block. The old side-valves are removed and lengthened push-rods are inserted in their place, and by utilising off-centre rockers to increase the valve lift, the head greatly increased the breathing potential of the engine. The exhaust outlets were widened, and on the right, a 1919 single Rayfield side-draught carburetor feeds the engine.

Frontenac didn’t just make heads. They also marketed radiators (see front of car), lowering kits, exhaust manifolds, steering wheels, clutches, hydraulic brakes, five-bearing counter weighted cranks, bodies, racing wheels, chassis, and ultimately, complete cars. ‘Fronty Fords’ as they were known dominated the field in small-town racing, and even managed to find prominence in the Nationals, most famously finishing fifth in the Indianapolis Race of 1923: 500 miles at an average speed of 82.85 MPH, and ahead of the Bugatti and Mercedes. Stirling Moss’ dad even raced a Fronty at Brooklands in 1926. Frontenac went on to refine their products and brought out a twin carburetor version of this head, a single overhead cam unit in 1922, and a hugely impressive 16-valve double overhead cam by 1924. The only time I see my Fronty head is in a museum.

Transmission: The Model T is perhaps famous – or infamous – for its epicyclic gearbox, which was proven technology in 1908 – even if by then obsolete with sliding-cog gearboxes already in use. But epicyclic or ‘planetary’ gears have one overriding benefit – simplicity. It pretty much has three moving parts, constantly engaged, And by stopping one or other parts of the gear-train by a series of drums, the various ratios can be obtained.

If you look in the cockpit you will see three pedals. The one on the left is the drive pedal. Push it down, and you engage low gear. Release it and you will pop back into neutral. To engage top, the hand-brake needs to be moved from the upright ‘neutral’ position and moved forward. The left-hand drive pedal is now free to move back – and you are in top. Actually, ‘top’ is simply ‘direct drive.’

The centre pedal is the reverse. Once in neutral (hand-brake pointing vertical) you press it and go into reverse. This can also be used as a brake. The ‘dab in, dab out’ system of drive control is actually quite useful. Skilled operators can rock a model T out of the muddiest hole, and three-point parking can be extraordinarily swift, but not for the faint-hearted.

The pedal on the right is the brake pedal, and is a simple transmission brake, working on a drum inside the gearbox, which is affectionately referred to as ‘The Hog’s Head’. The drums on the rear axle work in two ways – the inner single expanding system which is operated by the handbrake alone, and the ‘Rocky Mountain’ aftermarket system which works on an ‘External contracting’ system, attached to the brake pedal and a ingeniously designed compensator to keep the pressure equal on both sides.

The front wheels have no brakes at all. But in general, with much forward planning and a careful eye on the road and traffic, the powerful engine braking is more than adequate. Today, we tend to drive: ‘on the brake’. Back then, most people drove: ‘on the throttle’. As a side note, the distance of hazard signs from the hazard are based on the early years of motoring. When I’m out driving and see a ‘wiggly road’ sign, I slow down to be ready – and when I am at a safe speed, the hazard magically appears, exactly at the right time.

This article was written by Jasperfo

Was this article a help? Consider supporting the Flat-Spot by becoming a Premium Member. Members get discounts with well known retailers, a cool membership packet full of goodies and your membership goes toward helping us upkeep and expand on this great archive.